October 27, 2019 – January 19, 2020

Quietly and without much fanfare the North Dakota Museum of Art has been building a permanent collection that is becoming its greatest strength. With minimal financial resources the collection has evolved out of its exhibition program, gifts from friends and strangers, happenstance, sponsorship of special initiatives, by commissioning art, and occasionally buying on time. At the end of the 2018 fiscal year the value of our collection at the time of acquisition was $4,747,426, with another $316,350 to be added June 30, 2020. Many of these works have increased in value. For example, a Xu Bing calligraphy bought in the mid-1980s for $6,000 is now valued at over $360,000. April 2015, the Museum embarked upon a new program, the Art Makers Series underwritten by Dr. William Wosick, a diagnostic radiologist from Fargo. Because few professional opportunities are available for artists from the region, the program spotlights artists who reside and work here. The Museum Staff selects artists who seem on the edge of a breakthrough in their work. Four solo shows fall under the umbrella of the Commissions and Collections exhibition with two by current Art Makers: Vernal Bogren Swift and Donovan Widmer.

Donovan Widmer, 008101.02. 2018.

Sterling silver, ruby, vitreous glass enamel, velvet, wood, paper.11.25 x 11.25 inches

Donovan Widmer: Western Ideas of Beauty and the Role of Body Adornment

In this new body of work Donovan Widmer explores Western ideals of beauty and the role of body adornment as a form of personal enhancement — a way to transform the wearer into their idealized image of beauty. Using traditional metalsmithing techniques such as vitreous glass enameling, chasing, and repoussé, he produced this series of brooches that also harbor medical conditions that debase conventional ideas of beauty.

Artist Donovan Widmer is a jeweler and metalsmith who moved to Grand Forks in 2004 to teach at the University of North Dakota. He was appointed Chairman of the Department of Art and Design in January 2017. Five months later, he and his wife acquired a new home in East Grand Forks, Minnesota: specifically, a home with the potential to house a private studio. November 1, 2017, Widmer was named by the North Dakota Museum of Art as the 2018-19 winner of the Art Makers Award.

Widmer received his BFA at Edinboro University of Pennsylvania and his MFA from the School of Art, Illinois State University. When asked why he settled in the upper Red River Valley, he replied, Once you get over the harsh weather and what appears as cultural isolation, you realize there are incredible opportunities here. It comes down to finding like-minded individuals who share your interests. The city is large enough to meet your everyday needs, and small enough to feel like your everyday activities can contribute to the betterment of community and I want to be part of that.

I reached a point in my career as an artist when I wanted to investigate new ideas. I felt my previous artworks were becoming formulaic and I needed to start a completely new artistic investigation. It is difficult as an artist to suddenly change everything and begin a new train of thought. This Art Makers opportunity provides the resources to make this shift.

Vernal Bogren Swift. Bovey, Minnesota and Haida Gwaii, British Columbia

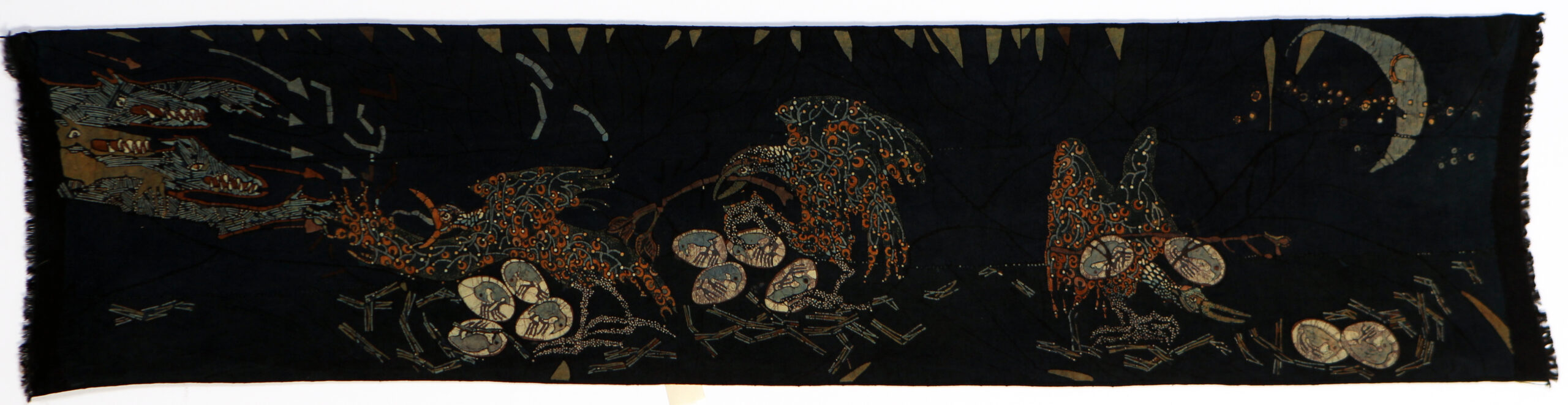

#11. Offering Fresh Milk to Whales. Scientists theorize that whales could have evolved from small land mammals like tiny deer, or from wolf like creatures with hooves. I cannot dispute the veracity of the theory, but would it be better to say all of it is a story, which humans do really well.

And you can’t dispute a story.

Meadowlark Buried Her Father Series, 2017-2019

Batik: wax resist on cotton, natural and synthetic dyes

North Dakota Museum of Art commission and collection

Vernal Bogren Swift: Meadowlark Buried Her Father

Meadowlark Buried Her Father is a collection of thirteen batiks inspired by the history of bone fossils in the prairie regions of North Dakota, Minnesota, and Manitoba. The pieces are realized in the form of batiks. The prairie fossils that inspire the batiks are mostly from the Eocene epoch of deep time. This is the time, millions of years ago, that follows the falling away of the dinosaurs. According to the artist, I focused on the Eocene epoch because, for one thing, the word means “Recent Dawn” which is charming in itself. Small animals flourished in this time and the air became sweet with the scent of flowers and grasses. Dragonflies were bigger than the horses. There were no humans, I do not know how big the bees were, but much of what began those millions of years ago has continued into modern time, with sizes varying. Refreshing after an age of dinosaurs…

Batik: As a batik maker, my work is influenced by Southeast Asian concepts, realized in certain design elements, technical details, and philosophical underpinnings. I am preserving the traditional art of batik while I interpret batik meaning in my Western way. Traditional Indonesian batik honors the fertile earth and the seasons of life. This is achieved by encoding symbolic messages, called motifs, into design for the cloth. Motifs always refer to traditions, regional geology, and the animals and plants familiar to the area. Batik cloth in this context is a symbol laden, deeply understood transfer of knowledge from the batik maker to the community.

In the 1800s, Dutch and Chinese traders married into Indonesian families and raised daughters who made the batiks known as Pekalongan batik, named for the a coastal port of entry by that name. Dutch batiks are influenced by European fairy tales and fields of flowers found only in Europe. Sometimes text is added along the outside edges of the batik. These European comforts are the motifs of the Dutch batiks. Motif is significant in understanding batik. It is the batik’s communication method and is often presented symbolically.

As a contemporary textile artist, I am intersecting the traditions of batik from Indonesia with my own batik motifs, encoding the beliefs of my own country and specific geographical region, with the animals and plants that live here. I use text in or near the batiks. The results are odd and fresh.

Motifs: The first motif in Meadowlark Buried Her Father is the fossil history of the prairies and the second motif is storytelling as a way of approaching what we call truth.

Not everything we hear is true, and in these days we have become wary. To complicate it further, discernment is complicated because our culture has a tradition of expecting honest reporting. We think people should “tell the truth.”

Truth is stapled firmly to time and context and culture. Pulled free of its staples, truth drifts. Emily Dickinson said, ‘Tell all the truth, but tell it slant.’ Success in presenting the truth comes when it is done circuitously. Storytelling. — Vernal Bogren Swift

Vernal Bogren Swift is a batik-maker and story teller. A graduate of the Cranbrook Academy of Art (MFA, 1996) in Bloomfield, Michigan, she received a Bush Foundation Artist Fellowship in 1998. Having lived on Minnesota’s Iron Range for decades, she sought and received a Jerome Foundation Travel and Study Grant in 1999 for an Australian trip to visit Shark Bay where ancient stromatolites, considered to be the “mother of iron ore,” are still found. Her choice of art forms, her fascination with pattern, and her receptivity to the myths of many cultures originated from years she lived in Africa and Papua New Guinea, and her study of batik in Indonesia. In her batiks she explores the relationship between geology and perception. Residing part of the year in Bovey, Minnesota, and the rest in Haida Gwaii, an island off the coast of northwest Canada, the artist has been deeply influenced by the way people see things depending on where they live. Her work is collected by the National Art of Gallery and the Textile Museum in Washington, D.C; Haida Gwaii Museum, Skidegate, British Columbia, Canada; and the North Dakota Museum of Art.

Vernal Bogren Swift. Bovey, Minnesota and Haida Gwaii, British Columbia

#12. Before There Was Any Land, There Were Birds Flying And Flying. They could not land for there was no land. So when Meadowlark’s father died, there was no place to bury him. After six days, Meadowlark buried her father in her own head. —Aesop, 500 bc

“And this is the beginning of memory. Before this, no one

could remember a thing.” —Laurie Anderson, The Lark, 2010

Meadowlark Buried Her Father Series, 2017-2019

Batik: wax resist on cotton, natural and synthetic dyes

North Dakota Museum of Art commission and collection

Robert Archambeau: Across Time

If you love the intense cloud pour every effort into its warm summer blood. Washed in stillness and beauty, this gathering of Robert Archambeau’s work from the past ten years speaks to an intensely lived life. Having celebrated his ninety-first birthday in the spring of 2019, this unretired artist spends endless hours in his clay studios at the University of Manitoba or up-country in northern Bissett, Manitoba, followed by long stints back home making small drawing and collage gems on paper. It might be 3:00, 4:00, or 5:00 in the morning before he crawls under the covers for a truncated sleep. Driven by a passion to create, Mr. Archambeau’s daily life illustrates the New Mexican critic Gus Blaisdell’s proposition that “passion is a kind of suffering that few of us can bear.” Across time, this artist has refined his art by repeating the same forms thousands of times over, by firing and refiring until the surfaces satisfies him in new ways.

The pots accumulate in every storage space he can claim as his own. Much like squatters who move onto land owned by others, his stoneware is scattered across several States and Canada. Endlessly working, he is known to throw two hundred pots in the six weeks before an exhibition. Once bisque fired in his Winnipeg studio, he completes the final firings in the nearby wood-fired kilns of friends, or in Iowa City, Moorhead, Minnesota, or Edwardsville, Illinois, where colleagues and former students own or run large wood-fired kilns. Sometimes Archambeau throws and fires new work in those same across-theborder studios for direct shipment to exhibitions in the United States. Occasionally he diverts his travels to Kalona, Iowa to cast lids for his covered jars at the Max-Cast Foundry. The forms of Mr. Archambeau’s ceramics are timeless, stretching across eons and cultures. The finished pieces are strong and sturdy, projecting great stature. They have both heft and mass, and, like the architect Marcel Breuer’s Whitney Museum, demand to be reckoned with. The outside of each pot is varied by repetitive sculptural markings made during the throwing process with any number of conventional and unconventional tools such as combs, saw blades, a Norwegian leather worker’s knife.

His glazes of grays, whites, greens, and blues, and the pinks and golds of sunset are transformed as the wood ash shifts onto and around the pots during firing, or as the fire itself dances about and across the pots. If the artist throws common salt into the kiln during the highest temperatures of the firing process, the stoneware takes on a translucent and slightly orange-peel-like texture—sometimes even that is sand-blasted away. And always, when back home in Winnipeg, the drawing continues, stacking up in cigar boxes that echo their size. The artist’s stash of beautiful papers — handmade, precious, and exotic — accrued over many years and wide-ranging travels. His materials and methods are complex and varied, the surfaces thickened with collaged gossamery bits of silk, or paper on top of paper. Not unlike his works in clay, Mr. Archambeau’s passion for surface also informs his drawings. He builds and defines his images with acrylic, pastel, graphite, charcoal, and picture framer’s gilt, plus colored inks. He abrades and scrapes back into the thickened drawing while the scratched-in lines might subsequently be inlaid with more ink. For example, the pinks emerge from brown ink as it fuses with washes of acrylic paint. And sometimes, the final, rigorously reworked surfaces are melded together with a top coating of clear matte acrylic or furniture polish. These drawings are the antithesis of Mr. Archambeau’s stoneware, illusive, delicate, intuiting only the suggestion of a vessel. It is as though the ethereal works on paper and the utterly tangible works in clay have begun a long conversation about the trueness of art. It is with great pleasure that the North Dakota Museum of Art accepts 166 drawings into the Permanent Collection funded by the Helge Ederstrom Endowment for acquiring works of art.

Mr. Archambeau’s processes are multifaceted, his wood firings and his works on paper labor intensive. Most importantly, this master craftsman possesses an extraordinary and highly developed aesthetic sensibility. Thus the exhibition gifts the viewer with art of rare and subtle splendor awash with stillness and beauty. No wonder Robert Archambeau is the first artist from Manitoba, and only one of two Canadian artists working in ceramics to ever have won the Nation’s greatest artistic prize, the 2003 Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts in Canada.

—Laurel Reuter, Director and Chief Curator North Dakota Museum of Art

Robert Archambeau was born and raised in Toledo, Ohio. Following four years in the Marines, he attended undergraduate school at Toledo University, the Toledo Museum of Art School and Bowling Green State University, Ohio, graduating with a BFA. He received his MFA degree from Alfred University in 1964. Mr. Archambeau taught four years at the Rhode Island School of Design before accepting a teaching position at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg where he chaired the ceramic program until his retirement in 1991, where he holds professor emeritus status. A frequent guest artist at colleges and art institutions, he has traveled extensively throughout the world. He exhibits internationally and his work is in several notable public and private collections with extensive holdings at the Winnipeg Art Gallery and the North Dakota Museum of Art.

Sarah Watts

Sarah gifted the Museum dozens of non-Western objects. Including the mask pictured.

Kurumba Antelope Headdress

Arbina tribe, Arabend, an area of Upper Volta

(now Burkina Faso) for the Comite ceremony, which comes every 60 years

19th – 20th century

Carved wood, traces of original pigment

72.25 x 11 x 29 inches

Gift of Sarah Watts